A start . . . in medias res

At Your Service

The impulse to serve—to find meaning in service to the needs of others—may connect the sacrifice of the past with your present circumstances and very likely with varying possibilities ahead. Your own sacrifice of time and energy in the form of study serves you, of course, but may well serve not only your immediate academic prospects but also countless others you’ll encounter in your chosen profession. In this regard, service becomes a distinguishing feature on our campus.

And service comes in many forms, thereby offering inexhaustible opportunities for a life of meaning. Indeed, service may be so malleable that it expands to include inanimate objects, investing, for example, even battered old bed carts from the student health center with the fresh gleam of purpose.

After decades of faithful service to temporarily bed-ridden students at the health center, these scratched, dented, and generally broken bed carts appeared to have given their all. With the arrival of replacement carts of recent manufacture, the old carts, friendless and drained of spirit, were free for the taking before their final destination on the scrapheap. I selected twenty, which was not an easy haul. Apart from transport, you can imagine additional problems involving storage and restoration.

A dose of sandblasting and powder-coating prepared the carts for the addition of Amish-built drawing boards that slide on top and adjust to a comfortable incline. Endowed with new purpose, these drawing-carts remain at your service for many years to come, and they further distinguish the programming efforts below through their utility as handy sketching stations.

With this spirit in mind, let me say for the record that their very presence among our collection of plaster casts is an open invitation to all (or maybe a summons to those inclined toward mindfulness and well-being, given the many studies that confirm the salutary effects of even a few minutes per week of art-making). Come draw whenever you please and for as long as you please. The carts, materials, and casts are waiting for you.

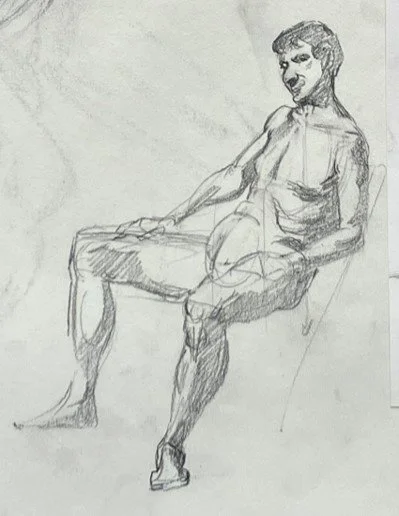

Like so. . .

With the carts and their adjustable drawing tops in place, new possibilities emerge. For years, I’ve considered how best to initiate the study of relief sculpture, but practical problems always intruded, namely how to access for drawing and sculpting purposes when most relief casts resist easy accommodation. Until now.

The carts are mobile, like most equipment in my drawing and painting classroom. With materials readily at hand for teaching and learning among students and their instructor, the space transforms—or permits the possibility of transformation—for those willing to engage.

Define engagement how you like; for me, an instructor of essentially novice art students, engaging with drawing necessarily summons abstract principles that most often require students to unlearn their assumptions of drawing, to expand their narrow definitions, and to embrace new concepts, methods, and techniques.

This transition from one approach to drawing to another effectively privileges formalism above all. By replacing a set of narrow assumptions with formal, which is to say structurally abstract, objectives that merge concepts, visual perception, and intuitions, students may experience drawing as more of a pleasure than a test of nerves.

Movement first (probably always)—fresh rhythms, as Leland Bell would say.

So much of what I do in class involves helping students engage drawing beyond merely outlining in heavy black charcoal. Identify—or rather identify with—the biggest or most emphatic movement; in other words, interpret drawing as an initiation of gestural empathy, which you represent with a segment—or segments—of line.

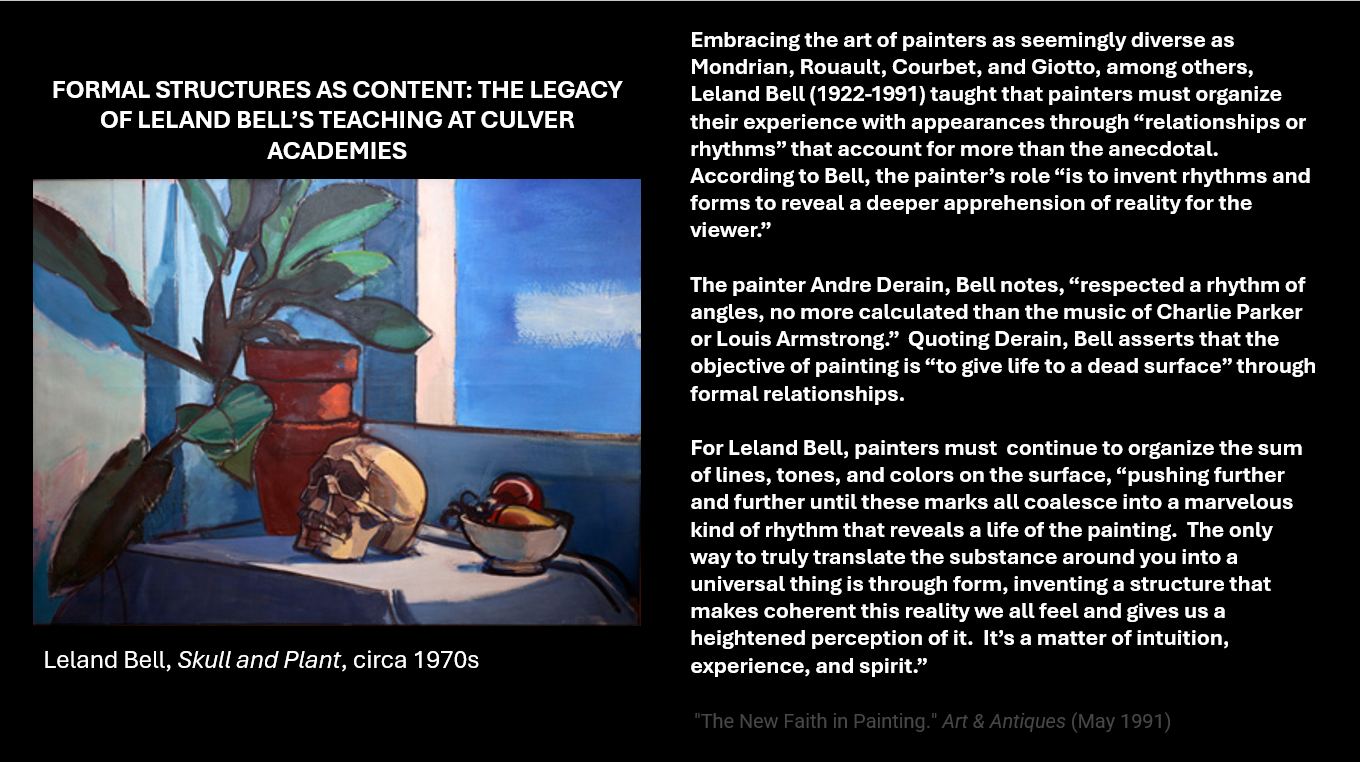

In the spirit of Leland Bell, a student in my beginning painting class struggles to respect a “rhythm of angles” by copying a painting by Andre Derain—while listening to the music of Charlie Parker.

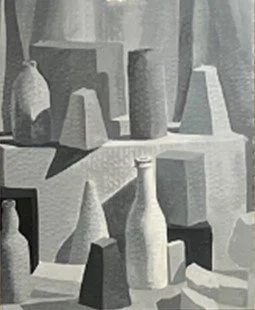

An exhibition of my students’ work (grades 9 through 11) demonstrating how things are rather than what they are; with every lesson, students learn how to perceive rhythmic movements, contrasts of tone, saturation, and temperature, and the matrix of geometric voids and volumes.

Examples to the left and below of first paintings from students in my foundations course; above, students in my more advanced painting course work from the live model. In all my courses, the lessons naturally build toward the constructive features of exemplary painters, past and present.

This first painting by a young student named Summer echoes the constructive beauty of Poussin and Morandi. I would happily listen to its visual music all day. In fact, I do.

And another student brave enough to attempt to copy Rubens’ Consequences of War applies strict formalism as he searches for key drawing and color relationships.

The Plaster Cast Collection

The ancient Romans practiced emulation (the Latin aemulatio) of great works of art as a means of surpassing their cultural predecessors, particularly with respect to the Greeks; the goal was not merely duplication of previous artistic achievements but rather the production of distinctly Roman monuments through the lively fusion of tradition and innovation. Roman architects, for example, often combined hallmarks of Greek and Etruscan buildings, creating astonishing architectural hybrids that served Roman political or religious purposes. Consistent with this ancient precedent of emulation, Culver’s collection of plaster casts, the acquisition of which has occupied my time for some twenty years, likewise provides my visual arts students the opportunity to inform their scholarly and artistic efforts through study and practice, as countless others have for many centuries.

Indeed, plaster casts have a long history as essential components of a visual arts education. In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance in Europe, young artists often began their apprenticeships by copying from the work of the master. After many months or perhaps years of drawing in this way, the apprentice acquired fundamental skills and knowledge prior to more challenging instruction. In later centuries, the guild approach evolved into a more formal program of study with the rise of academies of art. By the nineteenth century in Europe and the United States, official academic training had fully codified the expectations of a thorough education in the visual arts. Though a relic of the past, the old guild system continued to influence the training of art students, who first copied from the drawings or paintings of established masters prior to working from plaster casts of exemplary sculptures. When a student had achieved an appropriate level of skill and knowledge, he or she then proceeded to draw, paint, or sculpt the live model.

These art academies thus retained some features of the old guild system by training young artists through discrete stages of development. By the mid-twentieth century, the prevalence of abstract art as a means of expression precipitated the decline of traditional methods of teaching; the use of plaster casts fell out of favor, resulting in the wholesale destruction of plaster cast collections at major museums and universities. In the unsettling aftermath of two catastrophic world wars, plaster casts became emblems of a dysfunctional European tradition and thus easy targets for progressive educators, who literally tossed into dumpsters the collections of plaster casts they inherited from their predecessors. Such cultural bloodletting has its uses, perhaps, but so has the impulse to reconcile old and new.

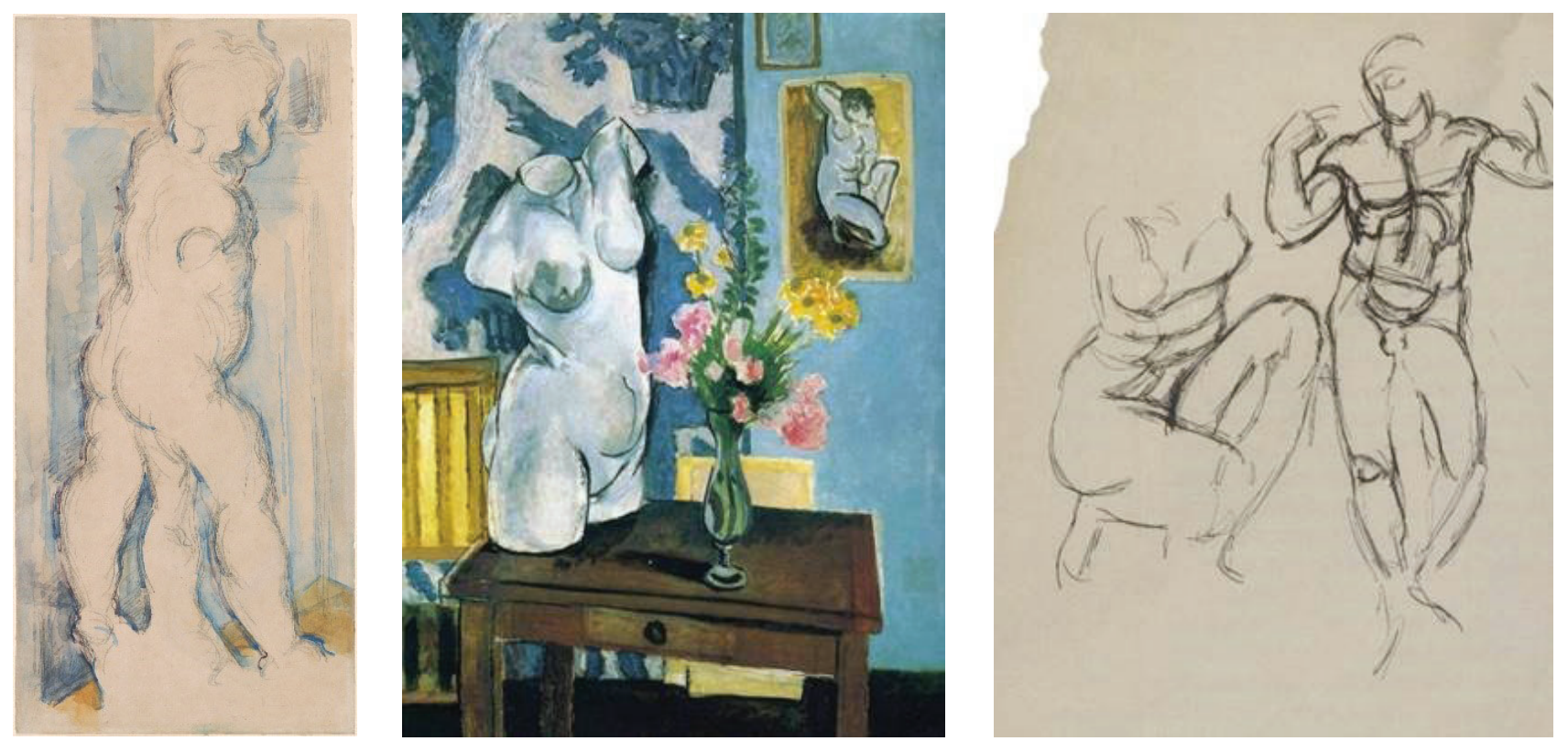

As an instructor of visual arts, my curricular intent blends the best practices of past and present by enabling the influence of Old Masters and modernists alike to peacefully co-exist in the same pedagogical context. Possessing enormous artistic integrity, Cezanne, Matisse, and Giacometti copied the work of the Old Masters throughout their lives, and they often drew and painted from plaster casts and figure sculpture.

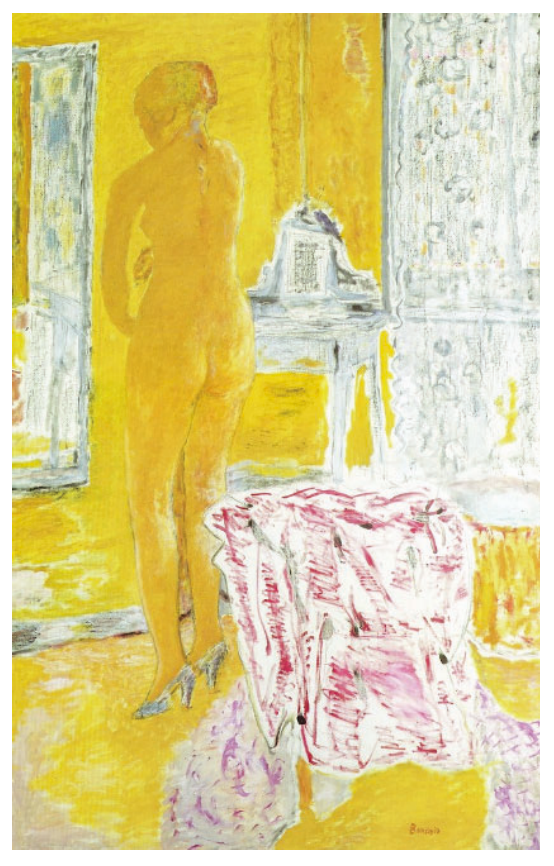

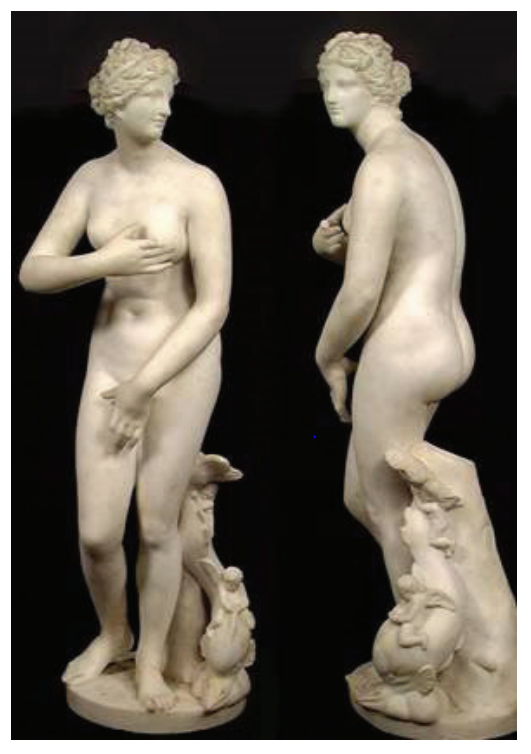

As the Roman practice of emulation so vividly demonstrates, tradition and innovation need not always contradict each other, particularly when the objectives (such as rhythm and balance) remain constant. This seemingly contradictory approach to the making of art has governed the theory and practice of our most celebrated artists. In her essay “Contentione perfectus: Rembrandt and Annibale Carracci,” Stephanie S. Dickey points out that Rembrandt and his fellow Dutch artists collected the works of Renaissance masters to assimilate the achievements of their predecessors in Italy: “Dutch artists, like their Italian counterparts, combined observation of nature with respect for pictorial precedent to create a style that synthesized tradition and innovation.” Likewise, Pierre Bonnard, a 20th-century painter with tremendous modernist appeal, constructed his daringly original paintings with intentional references to ancient sculpture, establishing an unlikely rapport between his idiosyncratic color sensibility and the Greco-Roman figurative tradition. His Large Yellow Nude, for example, borrows the pose and proportions of the Medici Venus, a Roman copy from the first century A.D. of a lost Greek original. For artists as revolutionary and diverse as Rembrandt and Bonnard, then, the artistic achievements of the past remained a vital resource that informed their own, highly innovative methods and artistic production. The same applies to my students, or should apply, if I can get it right.

With the passage of time, plaster casts gradually shed their association with the conformity of the official academic style of 19th-century France. Today, they are highly coveted artifacts that invigorate the art-making process. Museums, universities, and art schools from New York City to China have lately reassessed the cultural and pedagogical value of plaster casts, which serve the teaching and learning objectives of a diverse group of teachers, students, and institutions.

Some plaster casts from the collection at Culver Academies

. . . the lessons of Michelangelo, among others . . .

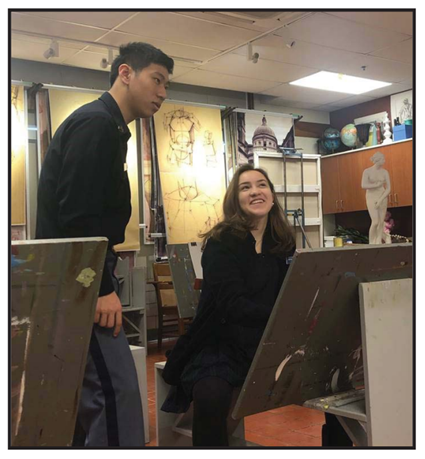

Also, advanced students in the year-long visual arts honors program may be invited to become teaching and learning interns; to the left, an honors student and teaching/learning intern helps a younger student consider adjustments to her drawing. Such encounters among students routinely promote optimal learning outcomes, not unlike the implicit results of mentoring with the expectation of graduated autonomy in the engraving below.

The School of Art, Benoit-Louis Prevost, after Charles-Nicolas Cochin, engraving, 1763

The engraving above from the eighteenth century concisely illustrates the stages of a classical visual-arts education. Note at the far left the youngest students copy from exemplary drawings with the guidance of an older student. In the center, young students who have learned their earlier lessons draw from a plaster cast of the figure while older, more experienced students again offer assistance. On the far right, the oldest students work independently from the live model, likely anticipating a subsequent critique from the master of the atelier. The implicit pedagogical model from this image is twofold: first, learning occurs within a continuum whereby initial efforts inform subsequent efforts as students overcome successive challenges through trial and error; second, the acquisition of skill and knowledge occurs most effectively within a collective of younger and older students who learn with and from one another. My efforts to construct Arcadia at Culver spring from this proven model of visual arts education, relying heavily on large- and small-scale reproductions of Old Masters’ drawings and paintings, plaster casts of sculptures from antiquity through the twentieth century, and of course the living model (when models are available). By virtue of their hard work within a highly intentional curricular structure, students in my classroom have the opportunity to accept and assimilate criticism, to renew their commitment to learning despite inevitable setbacks, and to ultimately enjoy the struggle to achieve by overcoming a sequence of art-making challenges. In this way, learning or, more accurately, teaching and learning may become central features of a happy life.

“a style that synthesized tradition and innovation”

“observation of nature with respect for pictorial tradition”

Culver students explore connections between drawing and sculpting with the use of plaster casts . . .

Visiting artist Alan Feltus teaching my students respect for pictorial tradition, Culver Academies, 2011

The painting Alan Feltus invented one afternoon while visiting Culver, 2011 (with an assist from my jacket, shirt, and tie that day)

My effort to sketch Alan while he rested after teaching my students, 2011

. . . and the live model, human or equine, as students have done for many centuries.

Students apply their understanding of history, literature, and art in Humanities Level 9 to determine how a cast from the Parthenon frieze and a passage from Sophocles’ Antigone reflect the same Athenian identification with the forces of order (cosmos) over disorder (chaos).

Aemulatio: the Lively Fusion of Tradition and Innovation in the Spirit of Ancient Rome

Tradition

The enormity of drawing as an art unto itself and as the structural foundation of all other visual arts is far beyond my capacity to express. Over time, maybe within the next decade if my health endures, I may capture some few aspects of drawing in this forum for students who share my interests.

My introduction to traditions of drawing and painting began with Joe Funaro, who studied with Deane Keller (the father of Deane G. Keller). Forty years on I still learn from my few scraps of Joe Funaro’s classroom demonstrations, which I happily saved from Joe’s life drawing classes at the Paier School of Art.

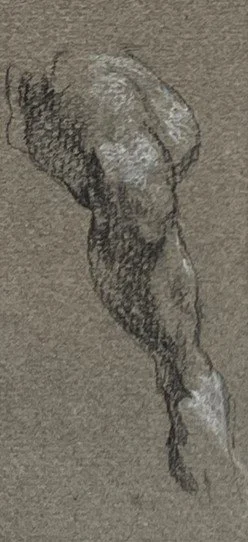

To the right is Joe’s demonstration offering me a way of understanding volumes through foreshortening, overlapping, and modeling form with a logic and economy of means that emerged in Florence in the early 15th century. For nearly four decades, Joe dutifully taught these lessons and many more, which he learned from his mentor, Deane Keller, in the 1960s and ‘70s, I believe. Looks like Joe was attempting to reveal the contrast of soft and sharp edges as well. He remained faithful in spirit and practice to the Keller approach.

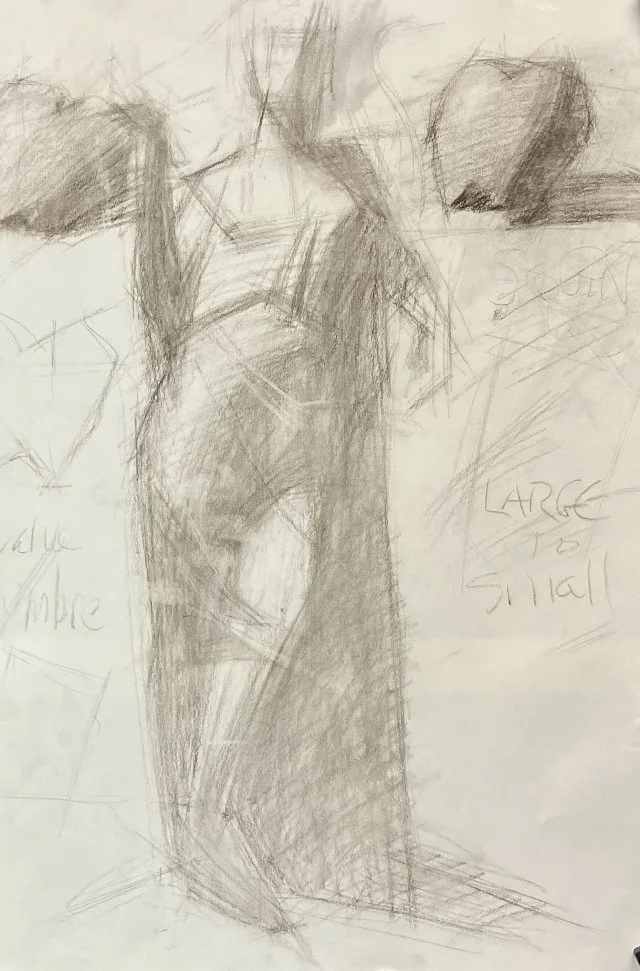

A ten-minute classroom demonstration by sculptor Stephen Perkins, December 2019, Culver Academies

Stephen Perkins demonstrating his drawing method (based on five decades of study with the likes of Walker Hancock himself), December 2024, Culver Academies

A ten-minute demonstration by my teacher Joe Funaro, circa 1984—the first of many unsung master draftsman I’ve encountered in my studies of drawing. Joe was a quiet, no-nonsense son of the old neighborhood in New Haven; his figure drawing, head painting, and portrait painting courses were legendary in our little school, where for several decades he diligently upheld the traditions that Deane Keller had taught him.

Within a few minutes, Stephen engaged traditions of representing gesture, proportions, placement, and tonal contrast. Also, as a governing principle, the written note “large to small” along the right side of the paper promotes the use of straight line segments, which in turn permit simplicity as a hopeful means of achieving precision.

Stephen’s drawing thus demystifies the mystery—the paradox—of drawing precisely by simplifying the information within your visual field. How can simplicity result in precision? My young student Ryan recently provided the answer for his classmates, “don’t see some things to see other things better.”

Clay Model, Prometheus, Stephen Perkins

Contact

You can contact me here:

email@email.com

(555)555-5555